Slurry is far more than waste or an unpleasant by-product. For farmers, it is a valuable resource. Using slurry wisely reduces fertiliser costs and improves soil health. It can also create new income opportunities. This is especially relevant in autumn, when fertilisation directly affects soil fertility and the yield potential of the next season.

One such opportunity is biogas production, which generates digestate as a by-product. Compared to raw slurry, digestate has a more uniform composition and its nutrients are more readily available to plants. This makes it particularly suitable for fertilising winter crops.

It is important to monitor application rates. Too much fertiliser in autumn can cause nutrient leaching and overly rapid plant growth. This reduces winter hardiness.

Why Is Autumn a Good Time to Use Slurry and Digestate?

In autumn, slurry and digestate play an important role in maintaining soil fertility and supporting nutrient cycling. After harvest, they help replenish the soil’s nutrient reserves and prepare the field for the next sowing.

When using organic liquid fertilisers, mineral fertilisers can be partially or even fully replaced – reducing costs and supporting sustainable farming practices.

What Do Paul-Tech Soil Station Measurements Show About Slurry Application?

Data collected by Paul-Tech’s soil stations confirm that when liquid fertiliser is applied to an empty field in autumn without a following crop, nutrients are washed out of the soil quickly. This approach is neither economically sensible nor environmentally sustainable.

However, when fertiliser is applied before autumn sowing and at correct rates, plants absorb the nutrients efficiently, leaving no opportunity for leaching. During the later decomposition stage, part of the organic matter stabilises into humus, which breaks down slowly and helps improve soil structure and water-holding capacity – benefits that last for years.

Practical Example: How Does Digestate Work on Winter Oilseed Rape?

Paul-Tech soil station measurements clearly demonstrate digestate’s impact on nutrient availability. On a newly established winter oilseed rape field, fertilisation was carried out before sowing, taking into account that the previous crop was winter wheat – its straw and roots also require nitrogen for decomposition.

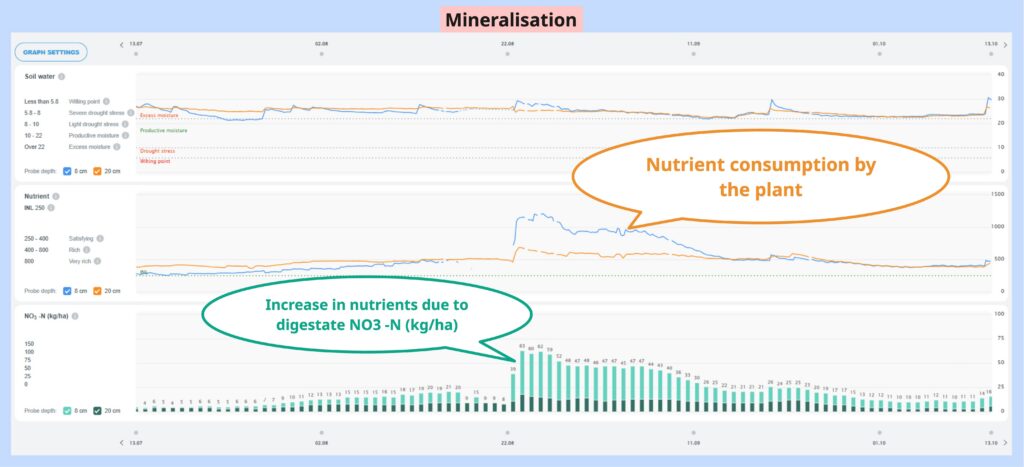

By mid-August, mineralisation alone had already produced around 20 kg/ha of nitrate nitrogen in the soil. After digestate application and sowing, soil station sensors recorded a rapid rise in nutrients within the top 8 cm of soil – exactly where young plants need them most. Only small amounts of fertiliser reached the 20 cm depth.

Nutrients were released and taken up intensively for three weeks and then at a slower pace. September and October rainfall did not cause nutrient flushing or leaching, which shows that the fertiliser was effectively used by the plants – a result that supports both higher yields and environmental protection.